Where Has Norm Quick’s Eyemo Gone?

(Originally posted on Canadianfilm.com in January, 2007)

Special thank you to Don Angus, editor of the Canadian Society of Cinematographers for publishing the following story which appears in the CSC January 2007 fiftieth anniversary issue – to visit the CSC website, please click on the logo below…

The missing item is a Bell & Howell, single-lens, 35mm motion picture film camera, the Eyemo 71. This type of camera was used exclusively in World War II by the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit, of which Norm was a member. Later on in the war, the Eyemo Spyder 71QM model would become the standard issue. The cameras were issued by the Canadian Army to the combat cameramen whose job was to record the war on film, both for military use and the folks back home.

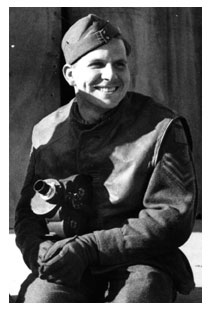

Norman Quick, a CSC Associate Life Member, is the last surviving cameraman from the Italian campaign, where he recorded the furious and violent action of invading Canadian forces advancing up the boot of Italy. Many of the stories that were recorded by the Film Unit have been preserved on motion picture film newsreels. The Unit produced 106 of these newsreels and they are currently being copied and restored at the Library and Archives of Canada.

I first met Norm while investigating an article that appeared in the Ottawa Citizen in May, 2006. At the time I was an acting archivist for the Library and Archives of Canada, and I was responding to a need at the Armed Forces Photo Centre (also known as the Joint Imagery Centre – JIC) of the Department of National Defence. Their film and video vaults were in great need of repair, and some of their holdings, motion picture films and videotapes, were beginning to deteriorate.

From this connection, I came into contact with the commanding officer of the Film and Photo section, Sgt. Serge Tremblay. During a tour of the facility, the conversation eventually focused on the old Army Film Unit that shot most, if not all, of the footage that was being held at the JIC. My interest in the early Film Unit must have made an impression because at the end of the tour Serge handed me a small piece of notepaper and said, “I have someone you should talk to. He is one of the cameramen from the Film Unit, and he lives here in Ottawa.”

I had always wondered about these WWII army combat cameramen. I was familiar with their newsreels, having worked on most of the 106 issues as a film conservator with the Archives. Who were these guys who shot with cameras instead of guns? They must have been a special bunch, people who would put their lives on the line for a few short movie clips.

I had to meet Norman Quick.

On the initial phone call, Norman was understandably cautious and reluctant to talk, but when I explained that I worked at the Archives and was interested in talking to him about the newsreels, he agreed to meet. Norman is an intelligent, strong-willed character with a sharp sense of humour that keeps you on your toes – you rarely get anything by him.

Over the next several weeks of visits to look at Norm’s collection of photographs and talk about some of his experiences during the war, the conversation eventually came round to Eyemo film cameras that the Film Unit used.

The motion picture cameras that were issued at the start of the war were all Bell & Howell Eyemos equipped with a single lens. The Film Unit later used the B&H Spyder, or Q model, with its three-lens turret. The “Q” allowed the cameramen to switch lenses quickly by simply rotating the turret, without having to reach into the equipment bag for another lens, and potentially miss an opportunity for a great shot.

As Norm describes them, the cameras were a part of you, and many of those within the Film Unit became very attached to their equipment. At the end of the war, however, the army repossessed the cameras and they were sent to Crown Assets for resale.

‘I'll give you a hundred dollars apiece’

“The cameras were put in a block of photographic equipment and this is how they were sold. And then people wrote in and made bids on it,” explains Norm. But after the war, a chance encounter by his brother, also a former combat cameraman for the army, led to an unexpected find.

“He (Charles Quick Jr.) is walking down Bloor Street (in Toronto) and he stops and looks into this window and he sees the green cases that our cameras were in, especially the Q models. So he went in and the one he spots has got my name on the box. So he says to the owner of the shop, ‘What are those?’ and the shop owner says, ‘I don’t know what the hell they are. I put a bid in to War Assets for photographic stuff and they sent me that stuff. I don’t know what they are.’ So Chuck says, ‘Can I take a look at them?’ The shop owner says sure, and Chuck opens one of the cases up and says, ‘How much you want for them?’ The shop owner says, ‘Make me a bid. Give me an offer.’ Chuck says, ‘I’ll give you a hundred dollars apiece.’ And the shop owner says, ‘Sold!’ So Chuck bought all six or seven of them, and sold them to the other cameramen that he knew in Toronto, and kept two.” One of the two cameras that his brother kept was Norm’s.

Asked why his brother did not give his camera to him, Norm replied, “I wasn’t using the Eyemo at the time. I was in 16mm then. So, what Chuck would do is keep two cameras loaded and grab one when needed. But when he died, I don’t know what his wife did with them.”

I made a mental note to follow up this lead and in the meantime began my research in locating as many of the Eyemo camera models as I could among those that might still exist. Apart from family members, I decided to check with museums, photographic stores, and on eBay. One of the museums was the Canadian Science and Technology Museum, and I made an appointment with Anna Adamek, assistant to the curator, Collection & Research Division.

In the museum’s inventory were five Eyemo cameras. The cameras came from all areas of film production sources: Crawley Films, the National Film Board of Canada, Associated Screen News and even from the Public Archives of Canada. (Many of the Film Unit cameramen found jobs after the war with the National Film Board, Associated Screen Industries and other film production companies spread across Canada.) But how would I know if any of these models at the museum was Norm’s original Eyemo?

The U.S. Army Signal Corps also used Eyemo cameras during the Second World War, along with the Royal Canadian Navy and Air Force.

Many of the Eyemo models appearing on the Internet today lack any provenance, or record of their origins. I felt the only resource left to me was to pour over existing photographs of the cameramen posing with their cameras and make note of any visible serial numbers, or other identifying marks appearing on the cases or camera body.

In most of the photographs taken of the cameramen posing with their cameras, the serial number is not visible. The Eyemo’s serial number is engraved on the side opposite the viewfinder, and most cameramen were photographed peering through the viewfinder, or holding the cameras in such a way as to allow a more pleasing photographic composition. I have yet to identify a Film Unit cameraman with a serial number on his camera.

Norm says his first camera came with a leather case. Many of the members of the Film Unit would mark these cases with their initials. Norman’s second Eyemo, the Q model, came in a green wooden box, which was marked with his name, N. Quick. Such markings could possibly have faded in time, or been removed by their new owners. It is hard to tell if any of the Eyemo cameras eventually found their way back to their original users.

EDITOR’S NOTES: Norman Quick joined the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit in 1943 and won commendations for his camera work on European battlefields. After the war, he became an NFB cameraman from 1945 to 1951 then rejoined the army for another 18 years before retirement in 1969. His father, film pioneer Charles James Quick, was associated in the 1930s with the old Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau, the progenitor of the National Film Board.

As a youth, Norm carried camera equipment for his father who, after starting his career as a projectionist at Toronto’s Bijou Theatre, helped film the five-reeler Polly at the Circus in Toronto in 1918 and later, in Trenton with the Ontario Motion Picture Bureau, was involved in making the great silent feature Carry on Sergeant in 1927. Two years later, director Frank Badgley brought Charlie to Ottawa to join the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau.

Dale Gervais has worked as a Film Conservator with the Library and Archives of Canada for over 20 years, and is currently involved in the preservation and conservation of Canada’s motion picture heritage. Some of the titles currently being preserved originate from well-known Canadian film production companies such as the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau, Associated Screen News, and the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit. His interest in early Canadian cinema has encouraged him to create a website, Canadianfilm.com that strives to celebrate the art, style and history of the men and women that recorded our nation’s cinema past.

Gervais says the Bell & Howell Eyemo71 was a spring-wind, non-reflex camera with 100-foot capacity (36′ per wind = 23 seconds of footage @ 24 fps). The Eyemo was first made by Bell & Howell in 1926 and was produced in a number of models, from a single-lens version through three different lens-turret models. The “Q” had a spider turret with accurate focusing through a rear-mounted prism, and a mount to take a 400-foot magazine.

Thanks go to Norman Quick for his time, photographs, and patience in writing this story. And to Charlie Ross for sharing his photograph and time. And to Anna Adamek for her extraordinary patience in allowing me access to the incredible collection of cameras at the Canadian Science and Technology Museum.

Should you have any information regarding the cameras or the Film Unit, please reply to;

webmaster@canadianfilm.com

Hello:

I own the Gallery: CinemaAntiques.com

If you know the body serial number of cameras you are searching for, I would be happy to see if we have any in our collection.

We currently have some war cameras available.

Hope we can be of help.

Hi Bill – thanks for reaching out. I will get back to you with some serial numbers and have a look at your cameras via your website. Dale